Between Land and Money: An Economic Consideration, Part I

Feb 14 2013

This is the first post in a series by John Bloom on money (global) and land-based (local) economic systems. While we are largely accustomed to the former, this historical analysis makes the argument for a new kind of economy, one which raises the profile of land-based systems to benefit and balance the global economy as we know it.

I recently visited the newly created Paterson Great Falls National Historic Park on the Passaic River in northern New Jersey. There stands a sign inscribed with the following: “Alexander Hamilton envisioned the great potential power of these scenic falls for industrial development.” Of course, this is intended as an encomium to the first Secretary of the Treasury of United States, and to the economic vision that he enacted on behalf of the hard-won and newly formed country. The Falls are magnificent, powerful expressions of natural forces. One can feel in the current an energetic transformation of the water as it falls seventy-seven feet, turns frothy white, and sends an uprush of mist and air.

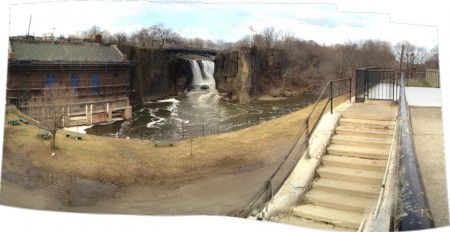

A panorama of Paterson Great Falls. Photo courtesy, John Bloom

The sound the Falls generate is a kind of white noise to the heavy highway traffic flowing by Paterson. Looking up from the effluence to its surroundings brought with it a chilling reminder of fallen industry in a town that the poetry of William Carlos Williams celebrated and economic history left behind.

Hamilton was an economic visionary. He saw nature as an underutilized economic resource and perceived the driving needs and opportunities of young untapped markets. Political revolution and the desire for independence constituted a seedbed for America’s version of the Industrial Revolution. This drive headed the US into the interdependent web of the global marketplace. For Hamilton, fixing the major structural debt problem in post-revolutionary America’s finances by stimulating industrial manufacturing was both motivator and strategy. Paterson, under Hamilton’s guidance, became the first industrial park. This venture was accomplished by the Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures [S.U.M.], a private corporation founded by Hamilton in 1791 with other investors. The success of the venture was supported by a New Jersey governmental decree of local and county tax exemption in perpetuity along with the rights to hold property, re-engineer the natural waterways, and raise additional capital. Not a bad deal—it became the working model for government-driven economic development to this day—except that we are running out of natural resources to exploit. The history of S.U.M. is a bit checkered and instructive. Having supported the engineering and construction of the industrial infrastructure in harnessing the power of the river, they faltered in their actual manufacturing business and five years later became instead property manager and executor of water rights for all the ensuing industrial development. Their work amounted to collecting rents.

While Hamilton operated in the name of public service, and he did much to right the economy, private enterprise was the game. The history of Paterson’s Great Falls was about new industries including textiles (especially silk), handguns and assembled AR-10 rifles, rope, continuous sheet paper, submarines, locomotives and, later, airplane engines. The industrial park along with its surrounding services, shops, and residential quarters became a place of industrial innovation and manufacture, expanding jobs suited to the skills of the influx of new workers from Europe, and was an easy access upriver economic partner to the vibrant marketplace of New York City. Well after Hamilton’s time, this growth also harbored the cross-streams of cultural, economic, and political worldviews that evolved in the later stages of the Industrial Revolution. By then, the human and social consequences of capitalism were in evidence. In 1913 in Paterson, with much wealth created but in private hands, jobs created for many but at the sacrifice of worker well-being, there was a protracted silk factory workers’ strike—it represented the voice of labor striving to find its place in the growing economy. It was an inflection point marking a downturn in Paterson’s economic arc, and a reflection of how disconnected capital could become from public service in the name of profit seeking.

The sub-story to this economic development was the untaxed right granted in perpetuity to industry to use the Great Falls as an energy resource with little regard for the resource itself. With the application of capital and ingenuity, energy was extracted from the water and transformed into power, power into manufacture, manufacture into markets, markets into capital, capital into wealth, and wealth into power. This is a story of economic manifestation in which God-given abundant natural resources are seized and under the control of capital, power, and polity. This disregard for the inherent gift of nature to all and the arrogation of private and privileged rights to determine its use is a one-sided self-interested, and shortsighted economic vision. The widespread implementation of this same vision has brought us to the brink of ecological miscarriage. While the natural gravitational flow of the river is used to generate the currency we call capital or money, nothing of that value is returned to nature itself.

In the story of how natural resources are used for profit, between land [representing all natural resources] and money, is an economic paradigm in need of reassessment and intervention. They are not the same. Their sources are different, their character is different, and to quantify the capacity of the land to support life, even to call it economic, is to sell its sustaining value short. In Paterson, what all that industry returned to the water by way of manufacturing and toxic waste was far from restorative, an insult to the living water and ecosystem. Hamilton’s fundamental economic assumption was an unlimited supply of raw materials and labor, inexpensive transportation and ever expanding markets. It was essentially a materialistic view, one in which man’s role was to dominate nature. His vision lacked any sense of or need for regeneration, and imperiously ignored any wisdom to be found with the processes of nature itself. There was, even until the mid-twentieth century, no need or incentive to consider used nature or waste as an economic resource in need of ingenuity and reinvestment. Paterson’s economy held through World War II but began to fade thereafter as did much of the textile industry and manufacturing in the northeast United States. The money economy and its attendant wealth accumulation sought ever-cheaper labor and production costs, and, tragically, cared little about the waste of people and place it would leave behind.

The polluted de-natured Passaic flows on as a man-made emblematic shadow of one end of capitalism. When capital or money is extracted from nature without regard for nature’s regeneration, without respect for its living system, nature is left to die. Capital moves freely about the world, across space and time; land and natural resources are rooted in place and geologic time. In a materialistic economy, time is money, and money used in this way sadly has no patience for the evolutionary pace of nature.

John Bloom is Senior Director, Organizational Culture at RSF Social Finance.