Economics for the Seventh Generation – Part I

Oct 30 2013

This essay was originally published in the Fall 2013 RSF Quarterly

“Seems like people don’t want to stick around another thousand years.” —Mike Wiggins, Tribal Chairman of the Bad River Band of Anishinaabe, on the proposed GTAC taconite mine, which will impact the watershed of the Bad River.

Let’s say that is not true. Let’s say that we are people who want to live in a way that restores our relationship with Mother Earth. We want to live in small, medium, and large communities, with a low fossil fuel impact on the world.

Ji misawaabandaaming, or how we envision our future, is a worldview of positive thinking. It’s an Anishinaabe worldview, coming from a place and a cultural way of life that has been here, on the same land, for 10,000 years. To transform modern society into one based on survival, not conquest, we need to make some changes. We need to actualize an economic and social transformation. Restoring an economics, which makes sense for upcoming generations, needs to be a priority. In our community, we think of this as economics for the seventh generation.

In our teachings we have some clear direction: our intention is Minobimaatisiiwin, a spiritual, mental, physical and emotional happiness—sort of an Anishinaabe version of Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness Index. Within our cultural teachings lie these Indigenous Economic Principles: intergenerational thinking and equity (thinking for the seventh generation); inter- and intra-species equity (respect); and valuing those spiritual and intangible facets of the natural world and cultural practice (not all values and things can be monetized).

After I graduated from college in 1981, I returned to my own community, the White Earth Indian Reservation in Minnesota (the reservation on which the federal government recognizes I am a Native person), and began a journey of working towards building this restorative economics.

Our work at the White Earth Land Recovery Project and Native Harvest begins from a cultural premise. We need to restore our relationship to place (we now hold 1400 acres of land as a land trust) and we need to determine what an economy looks like which is Indigenous. Our focus has been in the traditional economy, that which involves extensive subsistence agriculture and falls outside the definition of market economies. Food is at the center of this system.

Food Sovereignty

“I don’t think we can call ourselves sovereign if we can’t feed ourselves.” This is what Paul “Sugarbear” Smith told me a few years ago when I went to visit him in Oneida Territory, Wisconsin. I think he’s got something here and it’s worth looking into.

What is food sovereignty? The ability to feed your people. Let’s say that. This could be through your own growing and harvesting, or this could be through trade, if you’re happy with it and it’s working out for you. This is where we need to be, but certainly aren’t there now.

Let’s review how we got to our current situation.

When the Europeans came to America, they had no land, and brought very little food with them. The incidence of scurvy, diphtheria, and a whole litany of diseases, many of them linked to malnutrition, was overwhelming. We fed them, and taught them how to eat, here on this land, omaa akiing. For the record, Native people gave the world some big food. Corn and potatoes, for instance, make up a huge percentage of world food calories and nutrition, and represent immense value per acre. Not bad. We were good at this stuff. As an example, we Anishinaabe were the northern most corn growers in the world, pushing corn about a hundred miles north of Winnipeg, and our agro-biodiversity abounded. Overall, Indigenous peoples developed some 8000 varieties of corn, not to mention everything from pumpkins to chocolate. All pretty cool stuff.

Fast-forward post-colonialism and we are now a terribly dependent people, or peoples. By and large, we have ceased to farm our own foods and lands, all part of a logical consequence of theft, genocide, allotment, boarding schools, land alienation, and the lack of access to basic capital for even small-scale farming. We are net importers of food, and it’s costly. And even some of our largest tribal food enterprises like the Navajo Agricultural Products, Inc. and Gila River, produce food, not for Navajos, but for markets elsewhere. Thousands of acres of our tribal lands are leased out to non-Indian producers who ship across the world. And, in the meantime, we’re not looking good.

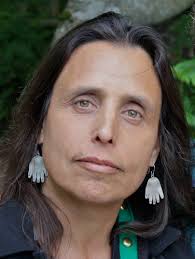

Winona LaDuke is an internationally acclaimed author, orator and activist. A graduate of Harvard and Antioch Universities with advanced degrees in rural economic development, LaDuke has devoted her life to protecting the lands and life ways of Native communities. In 1994, Time magazine named her one of America’s fifty most promising leaders under forty years of age, and in 1997 she was named Ms. Magazine Woman of the Year. She is Founding Director of the White Earth Land Recovery Project and Executive Director of Honor the Earth.