Technically, money is meant to be nothing more than a holder of assigned value and to serve as a means for facilitating the exchange of goods and services. However, money is also a complicated social reality, and it is encrusted with layers of perception, values, assumptions, and behaviors. For example, we say we invest money. At the same time, it is hard to imagine ourselves as not invested with the money. This is the essence of mutuality. More broadly, every transaction we are directly involved in has an element of self, regardless of how dispassionate we may be. If we are to understand our relationship to money and all the issues connected with it, we first have to look at our understanding of self. And there is no better or more ubiquitous herald of this complex of issues than the selfie.

The Selfie

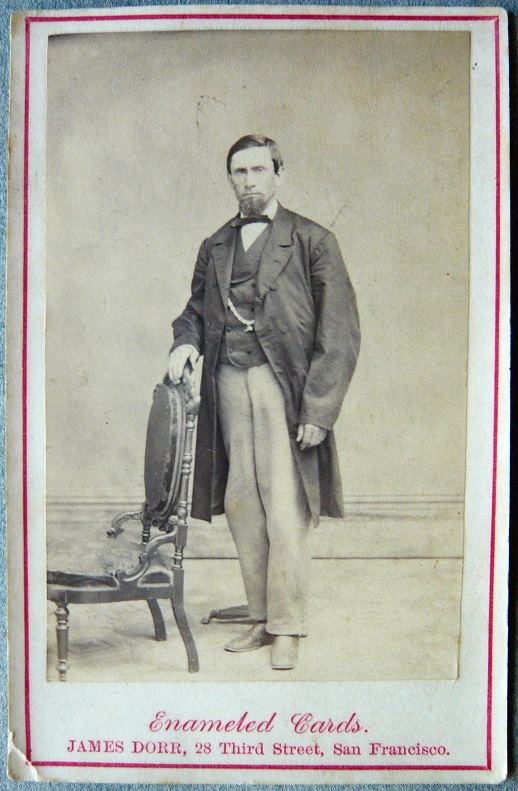

The practice of taking pictures of oneself via a smartphone or handheld digital device, a selfie, is distinguished from the studied art genre of self-portraits. With time, selfies may join that classification in name if not in physical manifestation. But for now, selfies serve a double function—as a self-generated affirmation of one’s existence, and as a social currency that has its origins in the mid-nineteenth century photographic form, the carte-de-visite.

Cartes-de-visite were 4-inch by 2.5-inch calling cards, first developed in 1845 by Eugene Disderi in Paris. They were extremely popular, and produced in large quantities to serve both relational and promotional purposes. Of course, the selfie is infinitely easier to create and distribute as it is essentially a weightless image. By necessity, cartes were produced in studio by a professional photographer with camera and replicable negative film. Through distribution, both forms follow and memorialize the pathways of relational networks.

Apart from its color and scale, the selfie has a different quality than the sepia-toned cartes. Selfies can be self-produced on demand, and inevitably have a relationship to place. In fact, the practice of taking a selfie is often most motivated by the desire to show where I am along with what I look like and who I may be with. My place in the world, as fleeting as it might be, is as important as my signature.

Fiat Currency

The selfie is a kind of fiat currency based on recognition and reputation. Its value emerges at the transactional level of send and receive, save or delete. The sheer ease of production, replication, and distribution assure a constant inflation-deflation that tracks with an inflated-deflated sense of self. We will likely never move past some need to assure ourselves of our own presence, beyond what a mirror might fleetingly reflect. To establish value for oneself through the circulation of selfies, as a way to hold oneself to accounts through the stories they tell, is something of an antidote (real or virtual) to how the fiat currency we call money actually works.

Missing from federal fiat currency is any reflection of one’s self. In fact, federal fiat currency is designed to deny a sense of self. Conventional money is intended to promulgate the sense of a centralized monolithic authority in which individual identity matters least. While this submerging of self creates extraordinary efficiency in accounting, it is also dehumanizing. One could look at the selfie as an attempt to individualize currency, and demonstrate its abundance.

The Problem of Representation

The selfie could be seen as an illusion of and allusion to the experience of self. The dislocation or remove from direct experience points to the problem of representation in which the image is mistaken for the thing represented—a kind of substitution. What implications are there in thinking that the image of oneself, the substitute, is the primary object by which the balance of our understanding of the world emerges? I can’t help but find this question essential to understanding how the next generation perceives itself in the world. Image-driven, what’s-my-brand consciousness abounds. Self-knowledge in ancient wisdom and traditions is replaced by brand management. This is very different than the experience of inner moral compass, the voice of which constantly asks, “Am I living as who my higher self imagines me to be?”

The selfie heralds a kind of double bind for individuality. While I can instantly represent and distribute my self-image and location at a particular moment, I can—at the same time—separate myself from that presentation. This is both gift and vulnerability. The gift of weightless distribution serves my memory and that of others. Vulnerability resides in mistaking the illusion for reality, and thinking that you are in relationship with yourself and others. This is one reason why we are more fragile than ever in how we stand in the world—a fragility that translates as loneliness, isolation, and separation in a supposedly connected world. So what do we do with this double bind?

Identity

Identity, the self we know to be authentic, is the last frontier of the world of commerce. The degree to which our identity is defined by the media, perhaps even claimed by the media, is the degree to which we are defined as consumers. I, for instance, buy commodities based on the values alignment I have with those products, which in turn is based on how they’ve been marketed to me. I acknowledge that this sets me up to be a commodity, the customer, defined by the constellation of bought brands.

The notion of commoditizing and annihilating the self by capturing it in a picture leads to a deeper attachment to self as a way to protect against a sense of loss. The fixed image is anathema to the ever-metamorphosing spirit-self that is the essence of each individual. One consequence of this process is a need for ever more selfies. So the ethereal image of self abides as currency in the thin polluted air of our time—to trade or leave behind. The desire to be human, to be recognized by others, even the ability to recognize one’s self, all are getting lost in the selfie transactions for which there is no accounting and no bottom line.

Money as a concept is a tool of accounting and economic exchange. But the way we have come to use it is a reflection of the transactional self—all consuming, identity bearing, entirely virtual, and moving boundlessly across the world. It might seem a contradiction; but the more we picture ourselves, the more invisible we become. We mistake ourselves for our shadows as Plato framed it in his metaphor of the cave. Where are we when we need us?

Blurred Distinction

The forces of illusory connection are strong and constantly reinforced at the speed of data, even as our capacity to connect in real time and place fades—despite the reality that such connection actually nourishes us. No doubt technology has contributed much to how we engage with and understand the world. Time and space have changed, as have our consciousness and expectations of the world. Our sense of self has shifted along with this evolution, but this has come with ever-increasing stress as we have to work harder to stay grounded. I cannot help but feel that the more we accept the selfie as feeding the brand of self, the further we are from the reality that forms our being. The more we trade in the self as currency, the more we commodify our self only to be stored and accumulated as bits and bytes of data, or unceremoniously deleted. As we convey what resembles us through a universal binary code, the more like money we become.

The distinction between money currency and the currency of self is blurring. As money is increasingly created and exchanged through digital block chains, so too is the self reimagined through the selfie with its own brand and value chain. What and how we value is linked with speed in exchange rather than depth of being. It is no wonder that we often feel defined by how much money we make or have, or don’t have. I am left with the relativist-absolutist question of identity. Finding a lasting definition of self, or even what a self is, is a difficult challenge partly because it is not a thing; it is unique to each of us. What this calls for is the peculiar human capacity for self-knowledge, freed of the projections, messages, and expectations that culture, polity, and the economic world have sent our way. The selfie is a signifier of absorption with the self and the epitome of self-interest, a posture that is closely shared with money currency. An unmediated and objective knowledge of self may be our prime antidote to the currencies of our time, and the key to being in the world with a more conscious and compassionate practice of interdependence.

John Bloom is the former vice president of organizational culture at RSF Social Finance.