New ownership and financing structures cut a path toward an economic system that can solve big world problems.

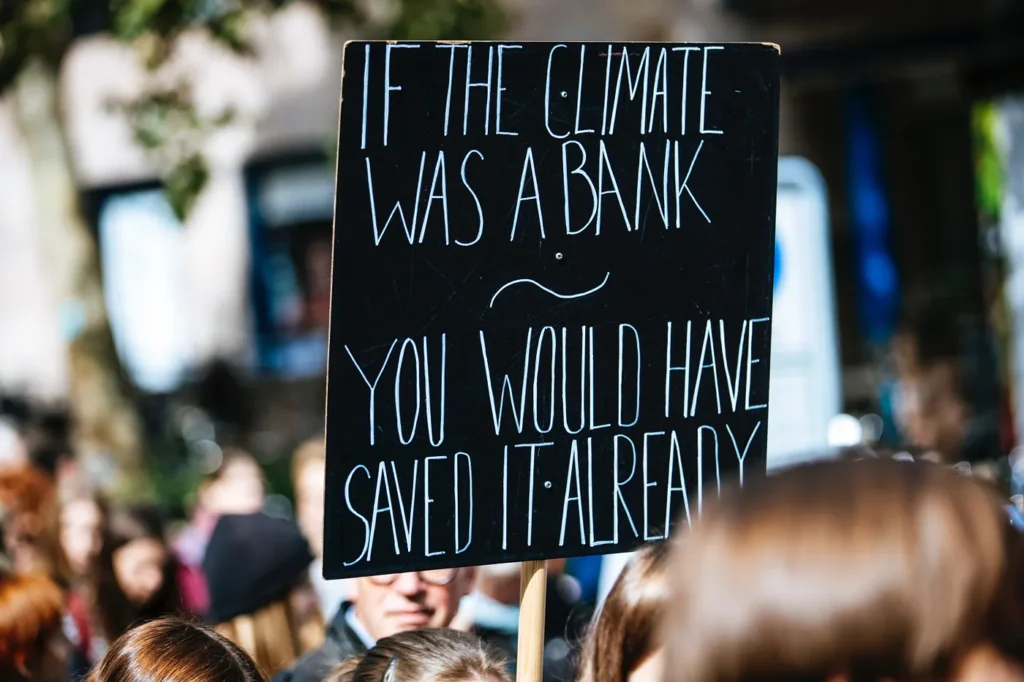

The way the world works with money isn’t working. That’s not news to anyone who is awake, and it’s true even for the tiny sliver at the top who believe it’s working for them.

To review: The climate crisis is here, and its intersection with social injustice is growing ever more obvious. Income inequality is widening. Trust in institutions of all kinds is eroding. The percentage of people who feel disconnected and disenfranchised is rising.

Business is one of the causes of these problems, and it must take a major role in solving them. But we can’t build the future on the scaffolding of the past. We need to redefine the role of money and investing, challenge the primacy of shareholder profits, and stop treating labor and land as commodities feeding wealth accumulation for the lucky few. Paradigms won’t shift if the incentives don’t. We need to rethink who controls and benefits from businesses, and create ownership structures that position profit not as an end but as an engine for creating social, cultural, and ecological goods.

In response to those needs, a grassroots global movement is emerging to develop and demonstrate mission-first business models rooted in stakeholder governance (decision-making based on the needs of all stakeholders) and to build a finance and legal ecosystem that supports them.

A movement takes shape

A confluence of factors is fueling this movement. One is millennials’ widely noted preference for companies with a purpose beyond profit-taking coupled with the massive generational wealth transfer the more affluent among them are about to receive. Other factors are more under the radar but probably more propulsive: The first wave of social entrepreneurs is approaching retirement age and looking for a succession plan that doesn’t destroy everything they’ve built. At the same time, these pioneers and succeeding waves of founders and CEOs are grappling with how to provide liquidity for themselves and their investors and protect their company’s mission while equipping it with a structure that enables growth and additional investment.

Even CEOs of the largest corporations are feeling the shifting sands, as demonstrated by the widely discussed Business Roundtable statement proclaiming that companies should be run to benefit all stakeholders, and the subsequent Davos manifesto echoing that stand. In other words, Milton Friedman was wrong. If that is true, the entire incentive structure of the business world needs revision or we will continue to have the same outcomes.

These concerns have already spawned the benefit corporation, the first widespread attempt to put up defenses around a company’s mission. Now available in 36 states, benefit corporation registration modifies a traditional corporation’s obligations with the goals of preserving mission through capital raises and leadership changes and creating flexibility in evaluating potential sale and liquidity options.

Provisions vary by state, but generally, benefit corporations specify their social and environmental goals, issue public reports on their progress, and may consider those goals along with profitability and shareholder value.

Benefit corporations are a real improvement over the dominant paradigm, but thoroughly reforming the way business works and establishing something close to a mission-first guarantee is going to require a more radical reimagining of ownership and control. Not romantic ideas we can talk about over a glass of wine, but practical, effective structures that allow a business to evolve over the long term while maintaining the primacy of stakeholder (not shareholder) rights. Fortunately, adaptable structures already exist, both in the wild and under development.

Mission-first models are plentiful

Purpose, a nonprofit with headquarters in Hamburg, Germany, and San Francisco, is researching and building a support infrastructure around a suite of mission-first structures it calls steward ownership. These structures have a history in Europe, and RSF Social Finance is hosting a Purpose team in San Francisco to collaborate on making them accessible to U.S.-based businesses.

Mission-first or steward ownership models share three foundational principles:

- Profits serve purpose — they are reinvested in the business, shared with stakeholders, or donated.

- Control resides with stakeholders who are actively engaged in or connected to the business and it can’t be purchased or inherited.

- Economic and voting rights are separate. Steward-owned companies can bring in outside investors as long as they don’t sell voting or controlling shares.

This form of ownership empowers companies to value long-term strategy over short-term profits. It protects companies from hostile takeovers, eliminates the potential for individuals to profit at the expense of the business, and prioritizes profitability in service to the well-being of the company and its mission, investors, employees, customers, and suppliers collectively. In other words, these structures allow decision-making based on the economic needs of the system and all of its stakeholders, rather than maximization of self-interest.

They also create community benefits. Steward-owned companies can invest a higher percentage of revenues in R&D, driving innovation. They usually pay higher wages, since they are not extracting profit. They are free to elevate social and environmental impact over growth. And their overall commitment to putting money back into the business makes them more resilient to economic and political cycles.

Purpose has identified several in-use steward ownership structures; among the most compelling are the golden share, perpetual purpose trust, and employee ownership trust models.

In the golden share model, a foundation holds a “golden share” that allows it to veto a change in the steward-ownership structure or a sale of the business for private profit. Those holding voting shares in the company control all decisions; these shares have no economic value. Golden share companies may also offer nonvoting shares with economic rights. B Lab General Counsel Rick Alexander developed the U.S. Golden Share charter in collaboration with Purpose.

In the perpetual purpose trust model, a noncharitable perpetual trust owns a majority of voting shares and appoints a board of directors. The trust redefines fiduciary duty, which can include multiple stakeholders, and prevents a sale of the business or undue extraction of profits. Profits are reinvested and shared with stakeholders. Outside investors can purchase stock and receive a dividend from the corporation, even while voting control is held in trust.

Portland, Oregon–based produce distributor Organically Grown Company (OGC) was one of the first to adopt this structure in the U.S. In July 2018, OGC bought back a large portion of shares from its stockholders and transferred them to the Sustainable Food and Agriculture Perpetual Purpose Trust, which now holds 100 percent ownership of the company’s voting shares. (RSF Social Finance provided a $10 million loan to help buy out OGC’s previous shareholders and recapitalize the business, plus $1 million in working capital.)

The employee ownership trust is a type of perpetual purpose trust that defines employees or members as the “purpose” of the business. Employee ownership in the trust is contingent on employment, and all privileges and rights end when a person leaves the company. Members can’t sell or transfer rights and privileges. While employee ownership may be the right solution for some businesses, there is legitimate concern that a transfer of power from shareholders to employees ignores the voice of other important stakeholders such as customers, vendors, and investors.

Another option is making creative use of the holding company structure. For example, founders can form an evergreen holding company (one that can’t be sold and does not have to adhere to the whims of Wall Street) that acquires majority shares in the business, and in exchange the founder (or founders) receives shares in the holding company. This can be a powerful mission-first structure for the original business and any others the holding company might acquire, since it safeguards control of the company. It does not, however, separate economic interests from voting rights.

Food businesses take the lead

Any business could adopt a mission-first structure: a tech startup, a consumer-packaged-goods growth company, even a multibillion-dollar public company (at least theoretically). Purpose has found interest in mission-first ownership from housing and community development, healthcare, publishing, and finance enterprises, among others. Our collaboration with Purpose, though, initially targets sustainable and natural food businesses. Many of these were founded by pioneers of the organic and regenerative farming movement, are already B Corps, and are focused on making positive impacts at the intersection of climate change and social justice. They are also feeling the full force of the succession issue.

That’s what motivated OGC. Previously employee- and grower-owned, OGC had been providing liquidity to its retiring farmer- and employee-owners for decades. For the prior 10 years, its employee stock ownership plan (ESOP) had allowed the company to fund share repurchases and redistribute the ownership to current employees. But with many founder-owners approaching retirement, OGC grew concerned about its ability to fund the generational transition without making a deal that would compromise its ability to invest in the business or would sacrifice its mission priorities. The perpetual purpose trust ensures that the company can continue to deliver positive economic, social, and environmental impact and maintain its independence in perpetuity.

OGC’s action is resonating with others in the space: a session on steward ownership at the 2019 Natural Products Expo West drew more than 65 people, including leaders of some of the country’s largest organic and sustainable food businesses. We’ve been exploring the possibilities with several of them.

One is a 25-year-old CPG business whose founders — 100 percent owners — are grappling with succession. They’re looking for a way to take retirement money out of the company they built and attract talent to run the business while protecting the mission indefinitely.

Another example is a flourishing regional organic food business. The founder brought in private equity to grow the business and is now seeing the shadow side, as the pressure for returns threatens the company’s mission. He’s looking to buy back ownership, ensure independence, and restore the company’s original sense of purpose. There’s also an organic body care startup that has avoided taking outside capital so far, but needs capital to take the next step and provide liquidity to founders who have barely paid themselves as they built their company.

A mission-first ownership model could be the solution for any of these companies.

The way forward

The challenges to building momentum for mission-first models are easy to see and will take real commitment to resolve. A report published late last year by RSF Social Finance and the Purpose Foundation, State of Alternative Ownership in the US: Emerging Trends in Steward Ownership and Alternative Financing, addresses these challenges and potential solutions, based on a year of field research and consulting with companies considering conversions to mission-first structures.

A major issue is that companies seeking to shift to a mission-first structure need access to patient capital deployed with the goal of optimizing financial return and impact in combination, rather than maximizing money out. Mission-first structures are not a hidden way to turn businesses into nonprofits — we recognize that everyone needs to make money — but mission-first models can’t thrive with returns-only capital. In a truly mission-first business, profits that exceed the immediate business needs serve the purpose and all stakeholders.

We also need replicable legal and regulatory structures. Right now each model is bespoke and applicable legal frameworks vary by state — a situation that leads to high costs. Finally, we need another 10, 20, or 50 businesses to take the leap, help develop the models, and share what they learn.

The commitment is well worth it. As Otto Scharmer, chair of the MIT IDEAS program for sustainability and cross-sector innovation and founder of the Presencing Institute, has said: “At the heart of our current predicament is a disconnect between the real-world challenges — the widening ecological, social, and spiritual divides — and the outdated economic models we use to respond to them.”

If we want to move to a regenerative economy and save ourselves from ourselves, one of the key shifts needed is a design for businesses based on the principle that the purpose of the business is to serve a mission. To do that it needs to be profitable, and to attract investors it needs to deliver a return. But making money for shareholders is not a mission in any real sense of the word, and centralizing decision-making power with shareholders leads to suboptimal decisions from a systems viewpoint. Mission-first ownership is an “associative” governance model that considers all stakeholders (including shareholders) in major decisions, enabling a fuller consideration of opportunities and risks.

If we want business to create economic, social, and environmental value, we need to toss more than a few paradigms out the window. What got us here won’t get us there: shareholder primacy needs to make way for stakeholder governance and redefining the role of profits as a tool to serve purpose. We made this system; we can unmake it. All it takes is a movement.

By Jasper van Brakel