The fund, initiated by an RSF Social Finance donor-advised fund holder, hands power to local leaders who distribute grants based on trust, communication, and a deep understanding of community needs.

The Southern Black Farmers Community-Led Fund is tackling a big systemic challenge—the need to support the region’s farming communities with more capital of all kinds—and it’s doing this work by putting the farmers in charge. In a turnabout from traditional philanthropy, the fund’s grassroots leadership council makes all decisions about grants and priorities.

“A lot of the funding experiences I’ve had in the past have required extensive reporting that became more of a load on top of the work that we were already doing. Because the Southern Black Farmers Community-Led Fund funding process is based on trust and relationships, it allows recipients to communicate using intelligent storytelling, which means we connect deeply to the ways we’re allocating the money to make a difference,” says Zel Taylor, Southern Agrarian Youth Network Coordinator of the Southeastern African American Farmers’ Organic Network, of their experience with the fund. “When we hear updates or learn about new ways we can contribute, it feels exciting because we know we have the power to move projects forward.”

SAAFON is one of seven organizations that anchor the fund, established by an RSF Social Finance donor-advised fund holder in 2020.

In fall 2019, the donor and RSF’s philanthropic services leadership team began to engage in a design process that would extend and deepen RSF’s shared gifting circle model. The donor was inspired by what they saw as strengths in the model: a place-based strategy, an emphasis on general operating support, and the ability of the participating organizations to grant to each other, supporting a regional or thematic ecosystem of partners. The donor also believed more robust grantmaking models, which strive to meaningfully disrupt traditional power dynamics in philanthropy and operate over longer time frames, are both possible and needed.

In 2020, fund adviser Kolu Zigbi developed a decentralized framework for the fund that, like RSF’s shared gifting circles, decentered donor expectations and centered community decision-making around capital.

The Southern Black Farmers Community-Led Fund saw these two goals converge to serve Black farmers and their local food economies in the Southeast to drive community wealth building and well-being in an area historically underfunded by philanthropy. The fund would also serve as a beacon to encourage a new generation that has been reluctant to take over farms in areas suffering from long-term disinvestment. The result is a collaboratively governed fund that is making progress on a massive challenge: transferring land, wealth, and knowledge from retiring baby boomers to younger generations.

Innovation: Out with paternalism, in with participatory grantmaking

Philanthropy has a long history of top-down decision-making when it comes to doling out funds. In most cases, the funder wields all the power over how their money can be used. This model has fundamental flaws. First, funders don’t typically have a full understanding of an organization’s needs and may dictate that their dollars support things like expanded programming—without considering behind-the-scenes needs like payroll or renting an office space. Second, funding is usually limited to one recipient rather than supporting an entire ecosystem of organizations that are essential to long-term community or sector vitality.

The Southern Black Farmers Community-Led Fund turns that paradigm on its head. Funding decisions are made not by the donor but by a leadership council comprising two representatives from each of seven anchor organizations—the Alabama State Association of Cooperatives, Federation of Southern Cooperatives, Mississippi Association of Cooperatives, National Black Food and Justice Alliance, SAAFON, and Southern Rural Black Women’s Initiative for Social and Economic Justice, all of which were members at the time of the fund’s founding, and the newest member, the Mississippi Center for Cultural Production (Sipp Culture). The group is empowered to divvy up available funds among its organizations or extend grants to other crucial community resources. It operates based on consensus, without direction from the donor, and its members hold each other accountable for achieving progress.

Zigbi says leading with trust and open communication has allowed members to fully understand each other’s opportunities and see where funding is most needed and can do the most good. She helped the fund’s participants establish their process by organizing presentations from leadership council members, who shared what they were working on and the challenges they were seeing in the field, and then facilitating deep discussions about needs and solutions. The group homed in on where the funding gaps were and devised a collaborative, high-level plan to fill them. Next the organizations detailed their needs in writing and submitted their requests for collective consideration. Then the group decided how to allocate the money.

Terence Courtney, Director of Cooperative Development and Strategic Initiatives for the Federation of Southern Cooperatives, one of the Fund’s anchor organizations, says the trust-based funding process makes each recipient organization deeply accountable to the others. “It’s not a naive or sort of kumbaya type of trust, where we scratch each other’s backs,” he says. “With typical programs, you get invited to write a proposal, you write it, a period of time goes by, and then you may get a call to talk about progress. Our process is much more rigorous in many ways while eliminating bureaucratic nonsense. We meet every month to check in with each other, talk about the projects we want to be funded, and ask tough questions. There’s no way to avoid scrutiny.”

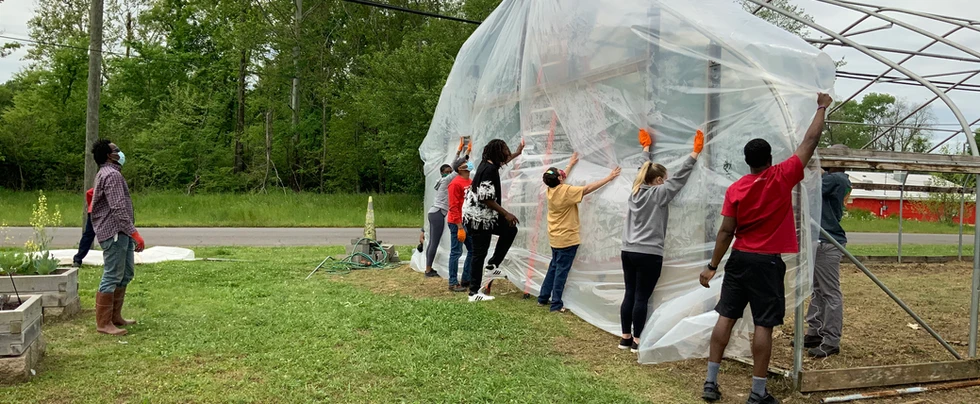

Taylor observes that “as a young farmer, having the opportunity to work with so many elders who have been doing this as their life work has been an incredible learning experience. Sitting alongside them, learning from their stories, and sharing space with other young folks doing the same allows us to build intergenerational relationships that support young farmers. We’re able to better understand what we are coming up against, create bonds, and call on their support to navigate challenges.”

Impact: Collective decision-making supports whole communities and builds connections across generations

The fund, which began with a focus on Alabama and Mississippi but has expanded throughout the Black Belt South and Southeast, awarded each of its anchor organizations grants of $100,000 in 2020, $50,000 in 2021, $50,000 in 2022, and $100,000 in 2023. The funding helped these organizations sustain their operations, provide technical assistance and direct services to their farmers, and continue to develop Black leadership in agriculture. The fund awarded an additional $1.75 million during its 2021–22 grant cycle and $2.035 million during its 2023–24 grant cycle. Those grants went to additional organizations for community revitalization, food system infrastructure, direct farmer support, and agrarian legacy extension projects.

“Black-led grassroots community-based organizations that work intimately with Black farmers in the South hold a lot of need,” says Southern Black Farmers Community-Led Fund Co-Chair and SAAFON Co-Executive Director Alsie Parks. “We’re holding a lot of people, a lot of farms, a lot of land. And through it all, we hold the understanding that while direct farming services are crucial, these farmers are more than just their operations. They are whole people who are the cornerstones of their communities.”

The fund takes a holistic approach to the communities it works with. Courtney says the greatest impact has come from resources given to sustain Black farmers and cooperatives that were on the edge in some way. “One example is our health and wellness center in Alabama. They serve mostly rural, low-income Black communities who need access to healthcare. They struggled for resources for a long time, especially since the beginning of the pandemic, which hurt their ability to bring in new people who could become sustaining members of the co-op. Our funding has helped preserve them and their crucial community work.”

The experience of participating in the fund is powerful, reports Taylor. “I deeply see the importance of Southern Black farmers having the autonomy to participate in grantmaking in the communities we are a part of. Being a part of this process has allowed us to support grassroots efforts across our network that benefit communities that are often overlooked.”