What Does Money Have To Do With Freedom?

Jan 23 2012

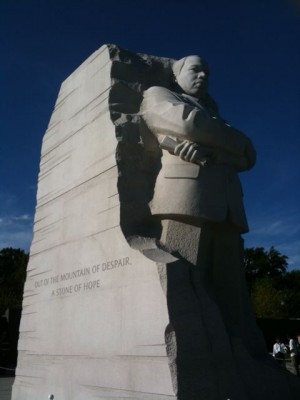

I have the audacity to believe that peoples everywhere can have three meals a day for their bodies, education and culture for their minds, and dignity, equality, and freedom for their spirits.

[From Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, Norway, 1964]

By John Bloom

Freedom is such a challenging word. It stands for a political view encompassing civil liberty; it stands in for the aspiration of the human spirit. What freedom means to me is personal. It informs how I go about the day as an individual and make my decisions, and it governs my communications and relationships as first principle—a capacity to respect the inner freedom of others even as I practice my own. Understanding what freedom means to others, as a right bestowed or limited by the state, as democratic practice, or as an inwardly determined guide to being, is fundamental to healthy relationships.

Given this brief background, I was bothered by a thought written by Harold Bloom [no relation], the esteemed author, in a recent New York Times article entitled, “Will This Election Be the Mormon Breakthrough?” [November 13, 2011, Sunday Review p.6] He wrote: “Obsessed by a freedom we identify with money, we tolerate plutocracy as if it could someday be our own ecstatic solitude.” If you have read the sentence a time or two, perhaps you are with me in my disturbance. Do we identify money with freedom? Is tolerance even a fair way to characterize our feelings about being ruled by the wealthy? And do we tolerate it because each of us secretly desires or imagines we could one day be wealthy enough to join the ruling class? I cannot think that participants and supporters of Occupy Wall Street share this implied aspiration. In fairness to Harold Bloom, the next sentence in the article links the experience of freedom with religious solitude. While it seemed to me either a non-sequitur or a leap based on unspoken assumptions, the swift shift is a microcosmic example of the muddled or manipulated boundary between politics and spirit. That blurring has allowed the political to pollute the domain of the spirit, and for spirit (or religion) to be used in the name of the political. Inserting money only further complicates the mix.

How can we possibly identify money with freedom, really? Money is an emanation of the material world moved by the inner forces of need and intention. While it has many and varied forms, money is a function, not a thing; money’s meaning is embedded in its service to economic life, that is to say as it supports the circulation of goods and services. When we treat it as a thing and tie our self-worth and identity to how much we have of it, we add to the complex that creates and “tolerates plutocracy,” and part of the complexity that sustains it. Money is no more a commodity than freedom. One cannot have money and be free of anyone else, because money in its true function holds or marks a value that is created through our economic interdependence. Freedom serves an important role in relation to economic life but should not be mistaken as an outcome of it.

Before exploring money further, I would like to return to the boundary between freedom as it pertains to political life and the freedom associated with solitude. The democratic principle of freedom, one person one vote, is a system of governance that is the result of community agreement—such as a constitution. Democracy is essentially a non-hierarchical form in that each member of the community is an equal of the others. And, it requires an “informed citizenry” to function effectively. What exactly does this mean? It is the responsibility of each individual member of the citizenry to engage in educating him or herself, to develop capacities of discernment, to seek insight into the matters at hand in order to effectively contribute to the democratic process. It also assumes that every member of the community has the capacity, if not the desire, for self-development. This responsibility for self-development, and how each of us designs that process for him or herself, what each of us wants to undertake and define as accomplishment is the evolution of individuality and the locus of spiritual freedom. This, I believe, is what Dr. King was referring to as “freedom for their spirits.”

To squelch this inner freedom, to organize a society in such a way that some individuals matter more than others, especially in the body politic, translates into laming that society’s economic well-being. What self-governed inner freedom provides the economy is people’s fresh ideas and insights that can then be brought into service to the community as a way to earn a living. Each individual has a need for right livelihood to use the Buddhist phrase. It seems that this human capacity, left free, is an infinitely renewable resource for reinventing the economy, governance, and culture. But it requires trust in others and sharing of power, an education that brings us together rather than driving us ever further apart in the division of labor, and a sense that there is something more than the material world at stake. What we have not yet resolved is how to organize our society to recognize and support such a clarity of function and principle. But Dr. King certainly had the audacity to believe that we could and can. Our interdependent existence depends on it.

John Bloom is Senior Director, Organizational Culture at RSF Social Finance.