Economics for the Seventh Generation – Part II

Nov 1 2013

This essay was originally published in the Fall 2013 RSF Quarterly

We did a study on the White Earth Reservation in 2008 where we interviewed about 200 households, and asked people where they shopped, when they did. We found that our community spent around eight million dollars a year on food purchases for households and tribal programs. Seven million of those dollars went off reservation to companies like Walmart, Food Service of America, and Sysco. On top of that, the money we spent on reservation was largely sucked up by convenience stores, where we purchased really cool stuff like pop, chips, microwavable pizzas, and baked goods.

So, what are the consequences of this?

First, we end up with a hole in our economy, the size of seven million dollars. This is a drain, well, actually a hemorrhage to be honest. The figure represents about a quarter of a tribal economy. Add to that the fact that we do the same thing with energy, representing another quarter of our economy exported, and furthermore a health services budget, which is, frankly, fed on dietary related illnesses (one-third of the Indian Health Service client population has diabetes). The hemorrhage grows. This situation means that we don’t have the local value multiplier effect, and we have little to no control over capital or the circulation of money in our community. The circumstances become worse as prices rise for the food we have to bring in. After all, that food has to move on average 1500 miles from farmer to table, and requires a whole bunch of oil from fertilizer additives to packaging. This results in more and more food insecurity, energy insecurity, and health insecurity. And, more climate change—maybe a quarter of the climate change is associated with unsustainable agriculture.

So, what is the solution?

This is the happy part. It turns out that our ancestors and my father had it right. My father used to say to me, “Winona, I don’t want to hear your philosophy, if you can’t grow corn.” Now that’s an interesting thing to say to your child. Well, I thought about it, and thought about it some more. And then, I decided to grow corn. Along the way, I became an economist who wanted to look at the systems that support sovereignty and self-determination, namely our economic system.

This is how it is playing out. Take my house for example. We’re an extended family of ten or so people at various times. This is a two deer, one pig, 100 hundred fish, ten duck household. This is complemented by 300 pounds of wild rice and corn, 200 pounds of potatoes, berries, maple syrup, squash, and a lot of canned goods. We grow, harvest, and trade this. I don’t grow potatoes because I know someone who grows them way better than I do. And, I don’t mess with chickens because the Amish are good at that.

Now, this means a lot of hard work. But, it also means I can keep my waistline somewhere I might be able to find it, on a good day. It turns out, these foods are roughly twice as high in protein, and two to three times more nutritious than anything you can get at the store. This has, in short, immense positive health implications.

Now apply that to 9,000 tribal members hanging around White Earth, and you’ve got a bustling local economy, if you work it right. Our plan is to grow as much traditional food as our ancestors grew. Over the past ten years, we’ve worked to restore Anishinaabe agriculture growing 800 year old varieties of squash, northern corn varieties (hominy or flint corn, with twice the protein and half the calories of market corn) and doing so, this year and next year, increasingly with horse power. Yes, horse power.

We sell these goods locally to create a multiplier, and then sell surplus to people who value Native food. This is what we are working on at Native Harvest.

What I know is that we are good at localized agriculture. While the paradigm of a “war on poverty” is creating a labor force focused on training and retraining my community for jobs which do not exist, or linking us to a dysfunctional economic system, we are intent upon shoring up that which we know can last for another thousand years: a self-reliant economic system that does not require massive inputs of fossil fuels, because, we all know that fossil fuels belong in the ground, not in our food system, and not in our air.

So, what is the value of this?

Well start with this, it’s intangible. Health is awesome. It’s also awesome to grow a squash that’s been around for 800 years or so, or some corn that might last in a time of climate change, because it’s not a mono crop, it’s short of stalk, and drought and frost resistant. Not bad, those ancestors. Then, think about how we are restoring some things which are sacred, and hopefully keeping them from getting genetically altered (like our battles to protect wild rice and corn, our mother grain). We’re building some sense of economic stability for the future, while we get some control over our health, food, and energy systems—these are all interrelated.

Food sovereignty is an affirmation of who we are as Indigenous peoples and one of the most sure-footed ways to restore our relationship with the world around us.

In this millennium, our people are told that we have a choice between two paths—one that is well worn but scorched, or one that is green. Our community is choosing the green path. That is the work of restoring Indigenous ways of living and land-based economics for the seventh generation. What will your community choose?

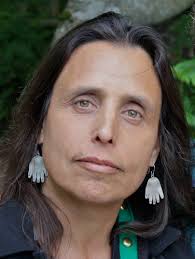

Winona LaDuke is an internationally acclaimed author, orator and activist. A graduate of Harvard and Antioch Universities with advanced degrees in rural economic development, LaDuke has devoted her life to protecting the lands and life ways of Native communities. In 1994, Time magazine named her one of America’s fifty most promising leaders under forty years of age, and in 1997 she was named Ms. Magazine Woman of the Year. She is Founding Director of the White Earth Land Recovery Project and Executive Director of Honor the Earth.